Happily ever never

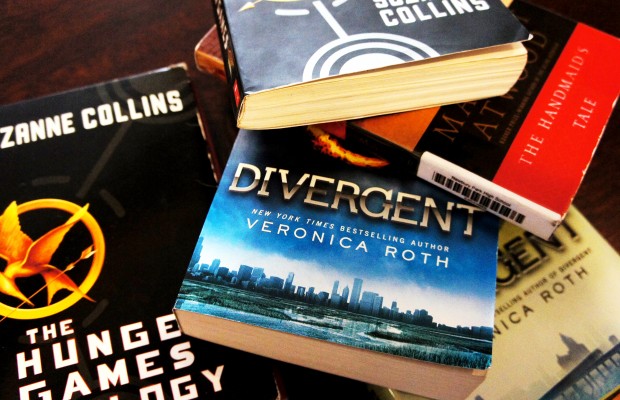

When we were little, all books, movies, and other forms of entertainment had their own “happily ever afters”. If high school English reading requirements have a purpose, it is to prove that this is completely false. Not all plots can end with the hero riding off into the sunset and the bad guys in jail or otherwise impaired, but the English curriculum has a vendetta against happy endings. Many of the books we read fall under the genre of “dystopian novels” – books specifically designed to make the reader contemplate what an apocalyptic future would be like. But if you’ve read one dystopic novel, you’ve read them all. So it comes as a surprise that in high school English, we’ve read not one, not two, but three dystopian novels. Without a doubt, this genre is overemphasized in the English curriculum.

I’ll give you a synopsis of every dystopian novel ever: a vague, undescribed event causes the world as we know it to go to hell. Some supremely powerful government attempts to remove all emotion and/or freedom from its people in the name of “peace” and “restoration”. The main character appears to be the only one that notices that anything is off, and by the end of the book, he or she ends up dead or submissive to the government.

The success of dystopian novels comes from their shock value. It is truly horrific trying to imagine living under such submissive conditions – the first time you read about them. However, by senior year, the shock value has disappeared. Reading the final piece of dystopian literature for my high school career, I find myself mentally yelling at the author about details she included not to advance the plot, but clearly to make us readers more depressed. Do we really need any more depression in high school?

I don’t know what our English teachers are trying to impress upon us with exposing us to this plot over and over again. Sure, Orwell, Huxley, and Atwood are the “trilogy” of the dystopian canon. But in twenty years, will our world really be controlled by a mysterious “big brother”? Will human rights as basic as when or when not to feel happy be taken from us? I don’t know about you, but if anyone tried to tell me I couldn’t smile on the streets, I would slap them. Maybe the cynical people are the most intelligent, and maybe I’m really dumb, but I don’t see the world coming to this state any time soon. If I’m wrong in twenty years, feel free to call me out on this.

I’ll admit, reading a dystopian novel or two probably won’t cause anyone to spiral into depression. But my favorite English assignments are the books outside the dystopian canon. These books (such as A Fine Balance, or the American novel we could choose during Junior year) are true to life – uplifting, distressing, and neutral events are equally represented, just as in reality. Yet, even when reading those books, some students in English class call them “sad” or “depressing” – and this is what is wrong with the dystopian perspective that has skewed our views even on other literature. Dystopian novels want us to see the evil in the world, but the genre should not be English’s sole focus when our world has many aspects, both good and bad.