A binational canal is necessary to fight climate change

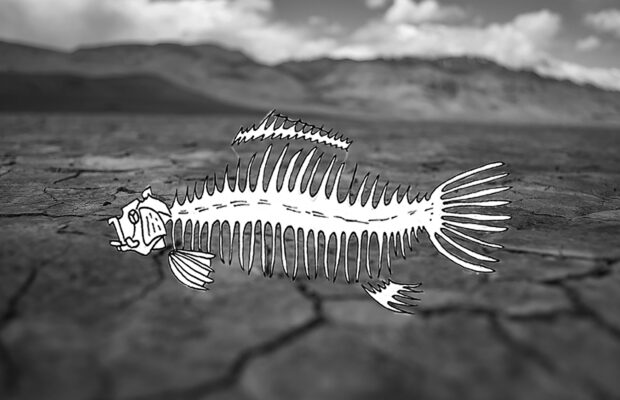

California’s Salton Sea was once a shining resort town of the 50s and late 60s; reminiscent of a Norman Rockwell canvas. The 21st century paints a destroyed ecosystem, with water levels dropping by 11 feet from 2005 to 2022, consequently exposing shorelines (playa). The playa harbors toxic dust, causing the prevalence of lung diseases and high asthma rates (22.3%) in the region.

The rise of the region’s lithium industry, dubbed “Lithium Valley,” is instrumental in California’s efforts to reach carbon neutrality by 2045. According to a 2023 study from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, the Imperial Valley sits above 3,400 kilotons of extractable lithium, equivalent to 375 million electric car batteries. However, the rush coincides with the Salton Sea’s unprecedented shrinkage. The already stooping water levels would be exacerbated by a looming reduction in the state’s Colorado River water allocation, along with the expected diversion of agricultural water needed for operating new lithium plants. Less water provided to agriculture will reduce runoff, the sea’s primary source of water inflow.

Currently, local nonprofits such as Comite de Civico Del Valle are pursuing legal action against the “Hell’s Kitchen” lithium extraction facility project. This is due to its potential cumulative impact on community health and air quality, resulting from the sea’s water depletion. This could potentially set a precedent for future litigation of other projects, negatively impacting and slowing global climate change efforts. To enable the development of the “Lithium Valley,” it is imperative that California lawmakers back the creation of a canal from Mexico’s Sea of Cortez to the Salton Sea. The canal could cover the toxic exposed playa without tapping into the Colorado River water supply.

In 2018, the state initiated an estimated $420,228,000 ten-year management program, to restore 30,410 acres of habitat and mitigate dust. However, according to a Nov. 26, 2023 Desert Sun article, there are 368 acres finished 2023’s out of targeted 11,500 acres. Failure to mitigate dust could lead to a public health crisis, as a 2022 University of California Riverside (UCR) study found the playa’s dust contained bacteria causing lung inflammation in lab mice; explaining the accelerated asthma rates. UCR professor of biomedical sciences, David Lo, identified an increase in asthma cases in Palm Springs, signaling the potential spread of playa dust into more metropolitan areas of Southern California.

The region’s water management, The Imperial Irrigation District’s (IID) annual water allocation is 2.6 million acre-feet (AF). 97% of the water is agriculture, with a third of it draining into the Salton Sea through runoff. The IID has 25,000 AF of water dedicated for non-agricultural use. This stifles the lithium valley’s development; the initial study on the Lithium Valley specific plan mentions requiring approximately 100 acre-feet (AF)of water. Tina Shields, the IID water manager comments water allocation, “It’s a zero-sum game. [If]lithium uses more water, that means there’s less for agriculture,” Shields said.

The definitive solution to the Salton Sea crisis is constructing a 120-mile canal from the Sea of Cortez to the Salton Sea. Project models such as the Sea-to-Sea binational water program aim to restore the sea to previous water levels within 15 years of construction, costing around $773 million. Lawmakers can help provide tax credits and project funding, assist with permits and help collaborate with the Mexican and federal governments. The canal is crucial in ending public health and litigation risks while advancing the development of the Lithium Valley. In hopes of painting a greener future, California lawmakers need to support the development of a canal from the pacific to the Salton Sea.