Two truths & a lie: How Facebook may be winning elections

Fake news used to be easy to spot.

“Elvis is alive – His Nashville hiding place!”

“Russia’s colony on Mars exposed?!”

“Bigfoot infests hikers with polio!”

Spared only a glance at grocery checkout lines, these tabloid headlines were obvious fake news to many people, unsupported by facts and filled with outlandish claims. Most also knew where to find real, trustworthy news with traditional sources like the Reuters News, Associated Press, Central News Network (CNN), National Public Radio (NPR) or Los Angeles Times.

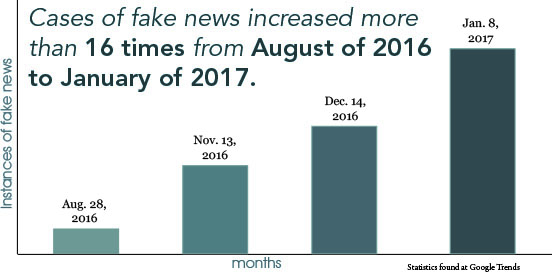

However, this line was blurred with the popularity of social media and the advancement of technology. We have witnessed the spike of fake news during the last election cycle. Spreading first from social media to its far-reaching audiences and occasionally even to top news sources, fake news about the presidential campaign and election this past year has been especially rampant. According to Craig Silverman, BuzzFeed News analyst, in an NPR “Fresh Air” interview, six to nine months before the November election, top election stories from 19 major media organization had greater social media engagement than top stories from 50 fake news organizations. However, just three months before the election, the momentum reversed, and fake news became more popular. Articles declaring things such as that the Pope endorsed Trump, that protesters had been paid by George Soros to join anti-Trump rallies and that Hillary Clinton had sold weapon to ISIS are just a few examples. Fake news had become so problematic that after November, concerns arose on whether fake news had tipped the results of the presidential election.

This rapid spread of fake news on social media has been facilitated by the “share” and “retweet” functions that allows everyday users to quickly disseminate links, videos and pictures. In a few hours or days, information and news can be dispersed through these sites and reach tens and hundred of millions of people. For the most part, our society has benefited greatly from them. With these features, news about the November 2015 Paris attacks spread across the world in a matter of hours with the #PrayforParis hashtag, and the image of a Syrian toddler’s dead body washed ashore brought the Syrian refugee crisis to the front and center of international attention. These are powerful tools that have revolutionized our information exchange process. They’ve made the world into a closer community. However, the problem arises when we start spreading news without fully understanding what we are sharing, as false stories are also shared with ease. According to a May 2016 Pew Research Center study, 67 percent of adults use Facebook, with 66 percent of those users obtaining their news from Facebook. This amounts to 44 percent of the U.S. population. When these many civilians are surrounded by potential fake news, it is no wonder that it has become a national concern.

The second piece of the fake news puzzle is the motivation: money. Fake news articles shared on Facebook posts often lead to websites displaying ads from online advertising companies, such as Google AdSense. For each view or click the website receives, its publisher receives a payment from the advertising company. Having a story shared around Facebook itself does not generate revenue, but the clicks do. This is how people such as satirical writer Paul Horner, who wrote entirely made-up articles suggesting Amish support for Trump or the paid protesters of anti-Trump rallies, made around $10,000 a month, according to an interview with the Washington Post. “I just wanted to make fun of that insane belief, but it took off. They actually believed it,” he said.

Even non-Americans have cashed in on the last presidential election. A study by Silverman discovered that teens and 20-year-olds based in Veles, Macedonia, a small town with a population of 43,000 who did not have any particular ideology preference in American politics, published 140 political websites promoting fake news about Trump. Whereas Facebook was the “driver” which allowed links to be “dropped” into pro-Trump groups, the actual ads on the sites were generating the money influx.

“There was almost an element of pride saying, you know, we’re here in this small country that most Americans probably don’t even think about, and we’re able to put stuff out and earn money and to run a business,” Silverman said in a December 2016 NPR interview.

Economics-driven fake new websites have reached such a point of abuse that in January 2017, both Google and Facebook amended their policies to mitigate the problem. Scott Spencer, Director of Product Management, Sustainable Advertising at Google, stated in a press release that the company had permanently banned 200 publishers for “misrepresenting content to users, including impersonating news organizations.” Will Cathcart, VP of Product Management at Facebook, also stated in a press release on the same day that changes had been made to the “Trending” feature algorithm: publisher names would be printed below headlines, everyone in the same region would see the same topics, and topics would be identified based on “groups of articles shared on Facebook instead of relying solely on mentions of a (single) topic.”

While these actions from search engine and social media companies are a large step forward in taking preventative action, 200 publishers of the 2 million websites that advertise using Google AdSense is barely a nick in this expansive business. We can not be passive news consumers either; we must bear some of the responsibility of investigating what we see and what we share.

Anyone can be guilty of being a perpetrator of fake news, spreading half-truths and unsubstantiated logical fallacies just to prove a point. Our tendency toward emotional decision making incites us to select only news that support our pre-formed beliefs and turn a blind eye to its accuracy and validity

In addition to this inherent bias that our minds possess, electronic ads and unreliable sources have been designed to blend in with other credible pieces. In a study conducted by the Stanford Graduate School of Education published in Nov., 2016, 7,804 middle school, high school and college students in 12 states were tested in recognizing sponsored content, verified social media accounts, credible sources at the top of Google searches and more. The results found that more than 80% of middle school students misidentified sponsored content as a real article, while less than 20% of high school students questioned the source and validity of a viral image with daisies claimed to be mutated from the Fukushima nuclear disaster. These discouraging numbers reveal the necessity for everyone, children and adults included, to learn how to look beyond tempting words and recognize and research the subtleties of fake news.

The desire to make money off internet will not end, so it is unlikely that fake news writers will abandon this golden market of fake news out of moral duty. However, spreading fake news has consequences beyond creating a lack of trust in the media. Fake news creates a climate where people don’t believe anything that they read for fear it was based in falsehood. Trust in credible news sources is vital in our democratic society and in holding the government responsible for its actions. When that trust is destroyed, it gives the government free reign to take any actions and portray news media’s reporting as fabrications of fake news to avoid accountabilities. It is time to re-endorse facts over emotions. We must demand all of America’s people seek out the truth in all its forms.

Pingback: Can You Detect False Information When You See It? – Living and Working on the Web