Heroin: The 21st Century Opium War

Long-term consequences of the short-lived high

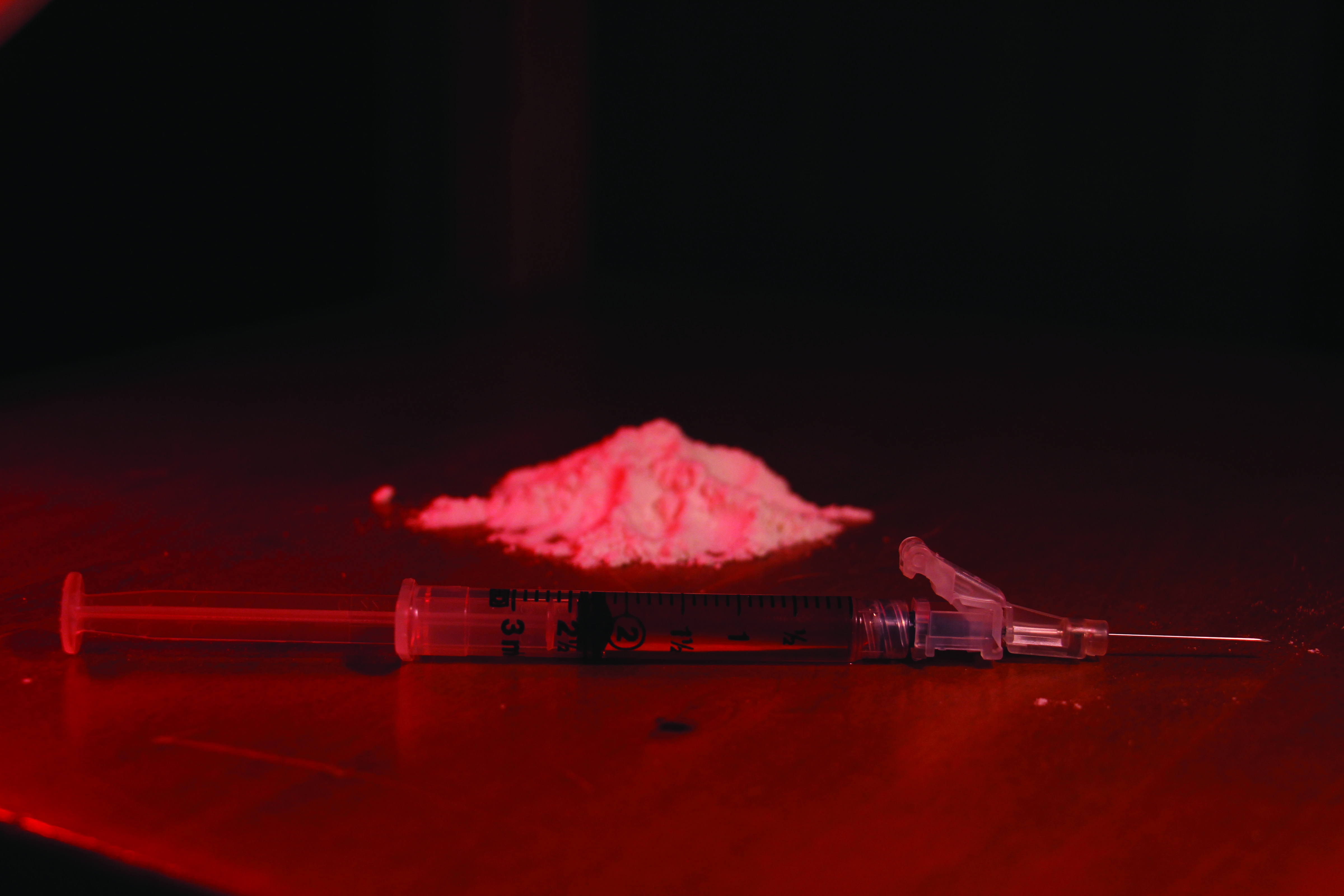

An overdose begins to kill long before a death takes place. The body is weak, shaky limbs reaching for a needle, for a shot of happiness that will slow everything down for a moment just long enough to feel euphoric. Blood rushes. Faces flush. But soon, it is not enough.Those shaky hands will soon long for more needles, until the dosage becomes too much.

Thomas Flores, junior, was able to stop before his addiction turned fatal.

Although his experience with alcohol and drugs began modestly in seventh grade, Flores’ substance abuse escalated in high school.

“I would smoke weed almost whenever I could get my hands on it. I didn’t have too much money on me, but whenever my friends had it, I would probably light up with them,” Flores said. “One day I smoked a lot of it and it really messed me up, and ever since then it was never the same, and every time I smoked (marijuana) after that I felt really weird, so I pretty much stopped smoking weed.”

In addition to smoking weed, Flores also was addicted to alcohol and cigarettes. After being suspended for five days for drinking on campus, Flores began working to get his addiction under control, but found it harder than he expected. He was mandated to join the district-wide BreakThrough program, an organization in Thousand Oaks dedicated to helping young people overcome their addictions. Even though he has completed his required time, Flores continues to attend weekly sessions because he still finds them helpful.

“We talk about our personality and about what can affect different people and how everyone’s brain is different. We talk about what’s good and bad in your life and what you can do to resolve the bad stuff and focus on the good stuff,” Flores said.

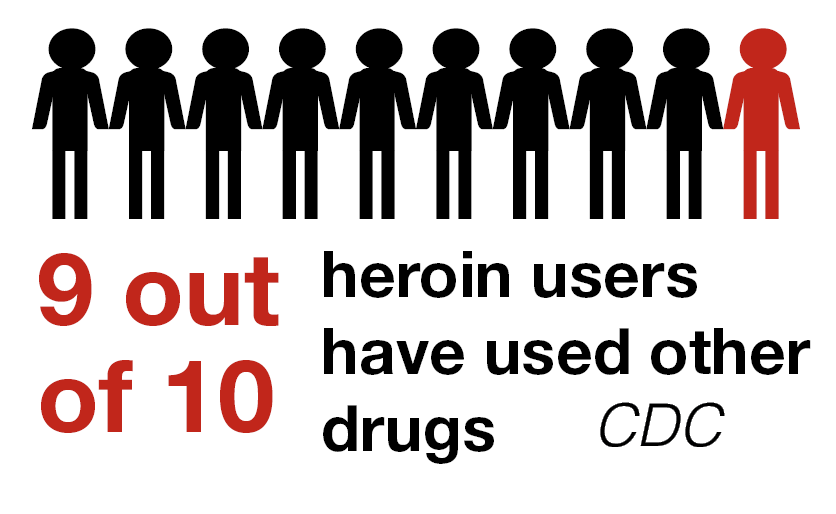

Fortunately, Flores was able to overcome his addiction. Tragically, that is not always the case. Zachary Young, another student who became involved with drugs, was not able to pull away. Like Flores, Zachary Young’s drug use began with marijuana, which then led to his heroin addiction. Despite the tireless efforts of his parents, friends, and counselors, he died from a heroin overdose on Sept. 9, 2016, at the age of 16.

“Heroin is a disease. It’s a drug unlike any other. Drugs are bad, you know, alcohol, pot, it’s all addictive, but heroin will just flat out kill you. The problem with it is that it takes over…It’s something that grabs you and won’t let go,” Robert Young, Zachary’s father, said. “It’s something you think about all the time. It lets you escape. It gives you a high like no other.”

Young described the social situation surrounding drugs in suburban communities. Even though the Young family did everything they could, from therapy to rehab to sports, the common availability of drugs made it all too easy for Zachary’s addiction to worsen.

“It usually starts at the cartel and then they find their distributor in California, and then they have local distributors in towns, and then they have people who know everyone in the suburbia, and then they work on the kids,” Young said. “It’s easy to get marijuana. If you can find someone with marijuana, you can get someone with other drugs too. My son started with marijuana, and he found other distributors through networking and finding out who the people were. He probably had four or five people selling it to him…when one would get busted he’d find another.”

Not only was heroin easy to find, but it was half the cost of pharmaceuticals, or prescribed painkillers.

“The cheap drug is heroin, so what happens is basically the Mexican cartel brings in all kinds of chemicals mixed with the opioid and they mix (heroin) with the pharmaceutical and other stuff, like household cleaners, and that’s what makes it so deadly,” Robert said.

According to the Center for Disease Control, 91 Americans die every day from an opioid overdose, a number that has quadrupled since 1999. The number of heroin-related deaths has also increased among 18 to 25-year olds. As reported by the Ventura County Star, heroin caused 33 deaths in 2015 in Ventura County alone.

“He was well-aware that it was going to kill him. It wasn’t a mystery that he was going to die. He already overdosed once,” Young said of his son.

Young believes the solution to the opioid crisis is to educate students about the consequences of drug abuse before they even occur.

“I think people need to realize (the problem) and be preventive. Get them aware about heroin, get them to understand heroin before they take it. You may be just a marijuana smoker, but the chances of you ever coming down after heroin are slim to none. You need to (be) preventive, not defensive. The only way to do it is education,” Robert said. “You’ve got to make sure they know how serious it is. It’s not if it’s gonna kill you, it’s when it’s gonna kill you.”

Flores believes it’s ultimately up to the individual to quit the addiction.

“If you really want to stop you can; it’s all in your mind, really. You just can’t give up and keep going with it,” Flores said.

The Body on Drugs

It starts with one hit. It can happen to anyone. It’s not usually intended to continue, but addiction can quickly follow, leaving users with a multitude of mental and physical ailments.

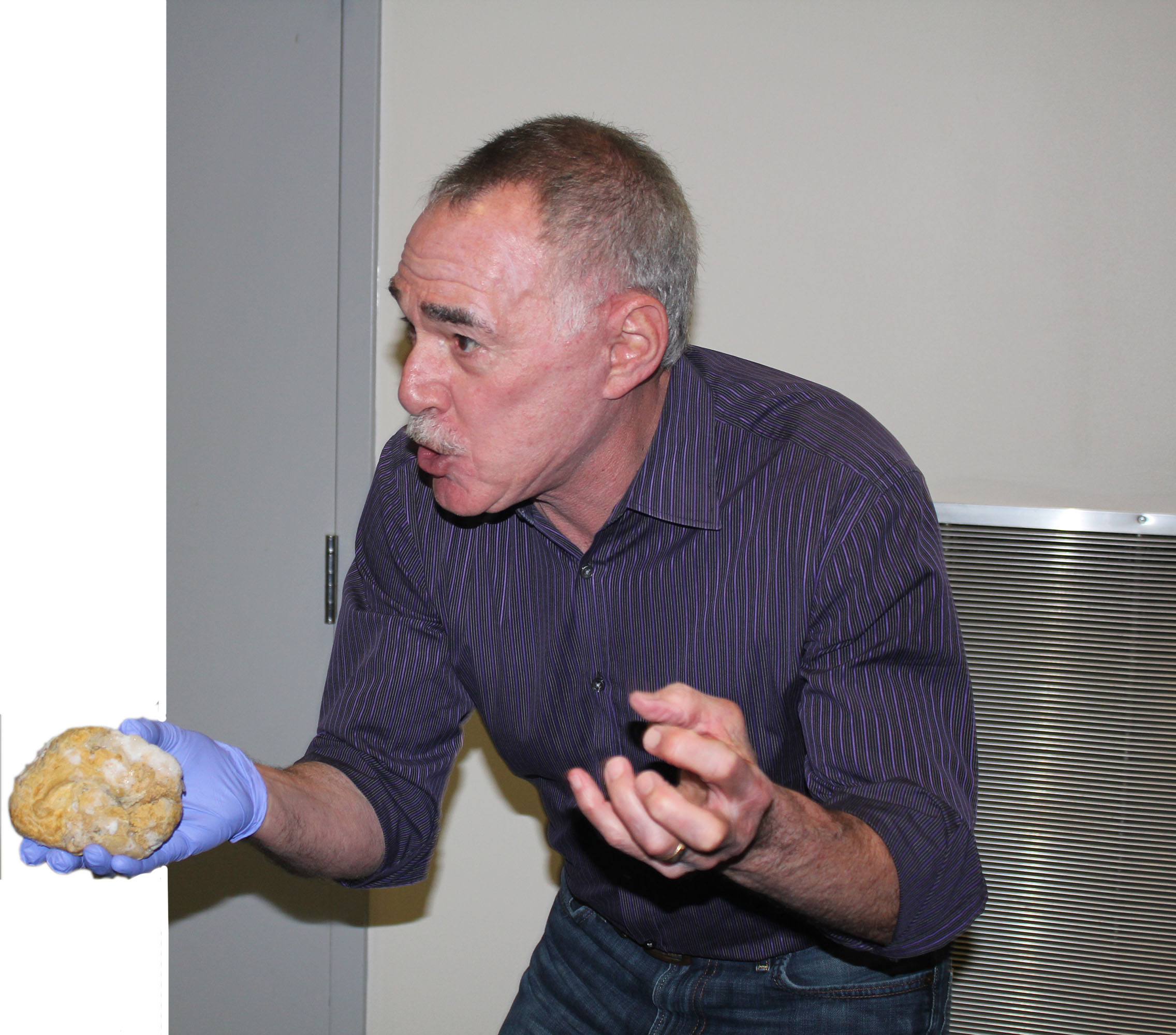

Dr. Victor DeNoble, a former tobacco industry researcher, continually speaks to a wide range of audiences on the science of drug addiction. He was one of the first to testify before Congress about his research, which proved the addictive properties of nicotine. Recently, he spoke at Teens Kick Ash, a Ventura County program dedicated to preventing adolescent drug abuse.

“Young people are much more vulnerable (to drug abuse),” DeNoble said. “ Your brain is developing, which means it’s faster. People under 21 process information three times faster than someone older than 21. This is good for learning, bad for addiction… You can be a drug addict at any age, but young people get addicted faster. That’s why drug dealers target young people. Your brain is wired to change. Nobody is immune.”

When drugs enter the body, they increase the amount of dopamine production in the brain, causing the user to feel pleasure. With repeated usage, the individual is motivated to feel the artificial high again, but eventually, the user’s body adapts to the excess dopamine. This builds a tolerance, meaning that the body has a reduced response to the drug. The user must take a larger volume of drugs to achieve the same high, which leads to overdose.

“Some people get prescribed prescription drugs for pain. If you use those drugs the way you’re supposed to use them, you won’t get addicted to them. What happens is people develop a tolerance, and instead of taking it once every 8 hours it’s once every 6 hours,” DeNoble said.

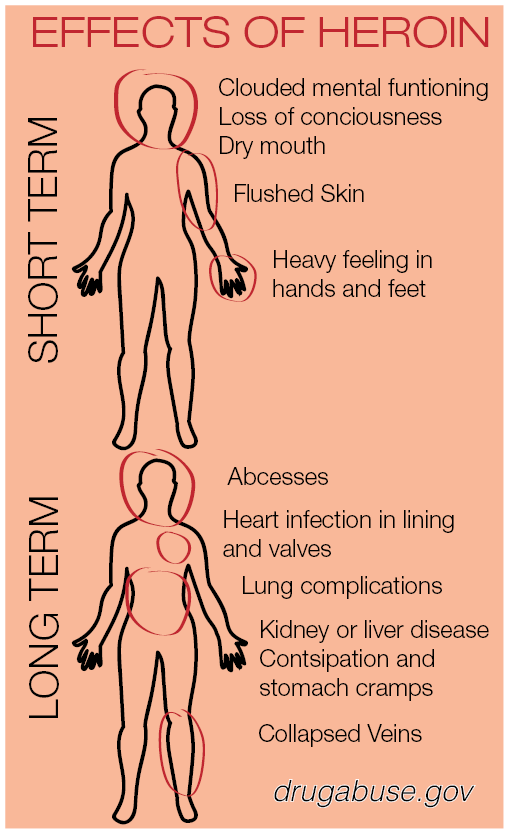

While the dopamine will give the user a rush, it only lasts for a few minutes. Negative effects will follow, and can last for hours after the “high.” According to drugabuse.com, while using heroin, users experience the short term effects of feelings of warmth and being flushed, a heavy feeling in limbs, a reduced sense of pain, drowsiness, sedation, and overall a lack of energy and enthusiasm. Over time, the body cannot always keep up.

“What happens with drug addicts is that they need to spend their money on drugs, so they don’t buy food. Someone who is first addicted to drugs may be slim or sleepy, but after a year, they’ll be very thin and have a lot of bruises. They stop brushing their teeth so they lose their teeth, their muscles will be taut because the muscles aren’t working. They have troubles going to the bathroom, because they can’t excrete the waste; it releases a toxin throughout their body,” DeNoble said. “It’s what we call a cascade of events. It starts with heroin, but it can lead to malnourishment and having a hard time with the physiological system.” Users also ex perience damage to their livers or kidneys, or contract infectious diseases, like bacterial infections or infections of the heart valve.

perience damage to their livers or kidneys, or contract infectious diseases, like bacterial infections or infections of the heart valve.

“Heroin is a narcotic, it slows down the entire central nervous system, and (addicts) die because they stop breathing,” DeNoble said. “The autonomic nervous system controls breathing and heart rate. When heroin gets in there, it slows down. When people take too much heroin or too much heroin and some alcohol, they will stop breathing.”

With the body adapted to drugs, withdrawal is an even more challenging process. Often mimicking flu symptoms, withdrawal includes restlessness and discomfort, a racing heartbeat, shaking, sweating, shivering, aching bones and muscles, diarrhea, vomiting and the inability to sleep. While most symptoms only last for one to two days, they can last more than a week. Making it out of withdrawal, however, is not always where a drug addiction ends.

“Your brain remembers what it means to be a drug addict. Say you’re an addict for five years, and you are clean for 10 years. Your brain will still remember what it’s like to be an addict and could relapse,” DeNoble said. “What I want people to remember, young people especially, is that everyone is vulnerable. Nobody can make you choose drugs. You choose drugs. It’s a disease, it’s a self-inflicted disease, but ultimately, it’s a choice.”

Course of Action

“Say no to drugs!”

In elementary schools, this common slogan accompanied students wearing red bracelets and ribbons to pledge their resistance. In high school, however, the message goes past the surface of “drugs are bad.”

Education and prevention starts at a young age, yet it isn’t until the ninth grade that students are required to take a health class. Lynn Baum, health teacher, covers drug addiction in depth, focusing on the myths surrounding drug use, how to refuse, and the biological effects of drugs.

Health classes emphasize the consequences of drug use with the hope of relaying to students how dangerous certain drugs can be. To do this, Baum uses a program called “Toward No Drug Abuse,” which, according to Baum, focuses on the myth that “everybody’s doing (drugs) when in actuality everybody’s not really doing it, and how that perception can lead to a self fulfilling prophecy of becoming a drug user.”

Along with this program, students learn refusal skills and watch videos from the perspective of prisoners who have been convicted of drug-related crimes. Baum also likes to work current events into the curriculum to help students see the reality of drug abuse.

Along with this program, students learn refusal skills and watch videos from the perspective of prisoners who have been convicted of drug-related crimes. Baum also likes to work current events into the curriculum to help students see the reality of drug abuse.

“I do bring up heroin because we are having a heroin epidemic right now,” Baum said. “We had a student not too long ago who passed away from a heroin overdose, a former student. And so we bring in the real life stuff, this is happening in our backyard, and talk about how to say no, how to combat that.”

Even though efforts since elementary school imbue the anti-drug message, Baum realizes that not all students internalize the information being taught. Despite the program, one of her former students, Zachary Young, still died from overdose.

Baum attributed part of the adolescent heroin addiction to the lack of education past ninth grade. “(Drug use) may not even be on their radar in ninth grade, but then they’re exposed by the time they’re in 11th grade,” Baum said. “Some kind of education on how to say no, life skills, something, I think should be added in 11th or 12th grade because now you’re going to go into the real world and you’re gonna be exposed to more, especially when you go to college. What are you going to do then? How are you going to say no at that time?”

However, Baum reinforced that no level of health education can ultimately stop all drug use.

“I always tell the kids your choices are yours. The choices you make are going to impact your life down the line. You choose the behavior, you choose the consequence,” Baum said. “It’s kind of like, you can lead a horse to water but you can’t necessarily make them drink. So the way I look at it more is for them to get the information, understand the information, understand what the consequences are, but ultimately it’s going to be their choice and I’m hoping that they make the right choice.”

Not only does drug education occur at a school level, but at a county level as well. Ventura County Deputy Joe Ramirez, has “reached out to parents and students about their drug use. (He has) also spoken to a few classes about drug abuse and what some of the consequences could be.”

The administration also occasionally brings in drug dogs to prevent illegal narcotics from entering the school, but they do not stop all drugs. While students cannot be punished for involvement with drugs on their free time, any time they are using drugs during a school-sanctioned event, including a bus ride to a game, can bring serious consequences.

“A student could be arrested for drug use or found to be in possession of illegal narcotics. The student will also be suspended from school,” Ramirez said. However, contact with loved ones or school faculty is essential to overcoming the addiction.

“(Trying to stop using drugs is) not easy and true friends will assist you every day … Remember you are not alone and there is always someone willing to help,” Ramirez said. He also recommends that students “have an open line of communication which will build a better foundation of trust between them and their parents. A student could also contact a teacher, counselor, administrator or me to assist them with getting off of drugs.”

Once a student reaches out and grabs the attention of an officer, teacher, or counselor, NPHS often refers people to the BreakThrough program. “That would be our first referral that we would make for them,” Kelly Welch, assistant principal, said.

The BreakThrough program is another resource used throughout the Conejo Valley to help rehabilitate students. According to Welch, the Co-curricular Committee usually encourages students to complete a minimum of six weeks in the program, where they conference with counselors and parents, participate in group counseling sessions, and learn about the effects that drugs can have on their bodies.

“Some students see it as effective, because they’re willing to change,” Lorena Rojas, a counselor from the program said. “We try to create a community where they feel like they belong, because I think a lot of students that do experiment with those things, they don’t feel connected with the school, or friends, and we try to provide this little space for them to feel like, ‘I can come to someone.’”

After the six weeks in the BreakThrough program are over, the committee comes back together with the student where they will decide on the next course of action, whether the student needs further counseling, and “help that student and that family come up with some sort of situation where we can continue to help that student,” Welch said.

Despite fears of punishment or disciplinary action from the school, overall Welch clarifies, “we want to try to catch every student to give them help, not to punish them. I’m not out there looking to punish kids or get kids in trouble or suspend kids. I want to help kids. We want to help kids.”