Behind juvenile bars, behind concrete walls

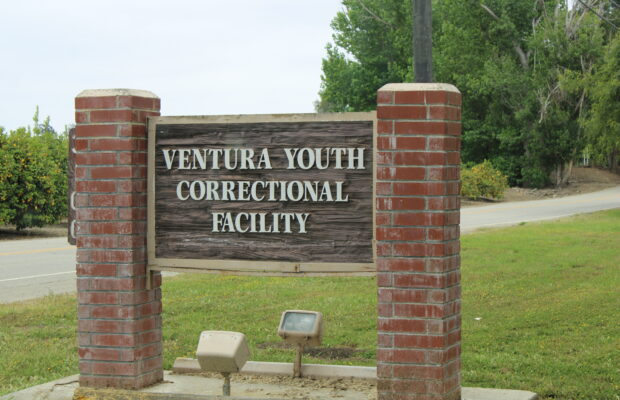

Drowned in acres of farmland in northwest Camarillo, the Ventura County Youth Correctional Facility closed its prison cell doors for the last time on June 30, 2023. The facility was one of the three state-wide juvenile prisons permanently shut down after Governor Newsom signed SB 823 into law in 2020. It has been nearly a year since the law disbanded the state-wide Division for Juvenile Justice, (DJJ), a system that operated for over 80 years despite numerous inspections regarding concerns of its hostile and violent environment. As a result, each California county now has jurisdiction over its incarcerated youth, meaning that in the case of Ventura, youth with long-term commitments, known as the Secure Youth Treatment Facility (SYTF), population, were placed under the responsibility of the Ventura County Probation Agency (VCPA).

The Ventura County Probation Agency’s juvenile facilities (VCPAJF), located in El Rio, Oxnard, operate at the local level and oversee young offenders aged between 12 and 17. However, the Special Youth Treatment Facility (SYTF) population, currently consisting of 19 youths, may remain in custody until they complete their sentence, which can last until the maximum age of 25.

Before the introduction of SB-823, the SYTF population was not under the VCPAJF’s authority. The probation agency’s previous practice was to house youth for a maximum of one year, limiting the VCPAJF’s ability to develop comprehensive vocational and rehabilitation programs. However, since the end of youth intake by the DJJ in 2021, the VCPAJF has been, and is still, shifting its approach. The intended realignment prompted a reassessment of the role of juvenile facilities and their correctional service officers, leading to questioning of the services they are meant to provide.

Precedently, youth in the DJJ had been subjected to life threatening issues of excessive force by staff and drug overdoses. Amidst this callous treatment and staff shortages, the youth were placed at risk by the uncertainty of the closure. With SB-823 it was recognized that “justice system involved youth are more successful when they remain connected to their families and communities,” (SB 823, 2020).

The Panther Prowler was allowed to visit and tour the facility in order to understand how the probation agency aims to define the term, “Juvenile Justice.” After meeting Carrie Vredenburgh, chief deputy of the Juvenile Services Bureau, and Declan Tormey, Division Manager of Juvenile Facilities Housing, the tour promptly began.

A concrete labyrinth: the booming slam of the prison door set the tone. Elaborate locking mechanisms, followed by sudden hushes, became consistent with each door’s meticulous opening and closing. The left side of the facility’s entrance corridor featured a colorful mural painted by the hands of inmates, with art representing various non-governmental organizations that have worked with the Ventura County Probation Agency Juvenile Facilities (VCPAJF).

Tormey, the Division Manager of Juvenile Facilities Housing, pointed to a painting of Elmo from “Sesame Street” plastered atop the concrete canvas, underscoring the grim duality of the juvenile justice system. A constant reminder that beneath the unjustifiable crimes, the chains, the fights, the pepper sprays and the strip searches, these were hurt children. It was reported in Dec. 2022 that 64 of the 83 youths in the facility had a known mental health diagnosis.

Across the nation, “Approximately 93% of detained youth were estimated to have experienced at least one of eight traumatic experiences compared with only 33% or less of the general population of youth,” reported the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration in July 2014.

The booking room featured a newly installed body scanner to mitigate the dehumanizing nature of strip searches. From April 2022 to July 2023, Ventura County conducted 425 strip searches on an average population of 71 youths. In comparison, Orange County’s juvenile facilities conducted 256 strip searches from July 2022 to Sept. 2023, with an average daily population of 171. The Orange County Probation Agency reported a decline in strip searches after installing a body scanner. However, data on the VCPAJF body scanner’s efficacy has not been released.

The 20-year-old juvenile facility was built for 420 youths, but with only about 60 currently living in VCPAJF, there is extra real estate. Former cell blocks were transformed into classrooms for Providence Court School, a fully accredited, genuine Ventura County Office of Education high school behind bars.

The “campus” had empty cells identical to those in the populated units. These cramped, unoccupied dwellings contained only a mat on an elevated concrete slab and a toilet connected to a sink.

In the seemingly endless hallway outside the repurposed unit, a single file line of about a dozen young prisoners headed toward the commissary, led by a probation officer with another trailing behind. The Panther Prowler was prohibited from speaking with any of the facility’s youth; they only communicated through silent stares.

Tormey’s voice called out to the last youth in line about paperwork and lawyers. The youth responded politely, “Thank you, sir.” While Tormey engaged the youth in conversation, Vredenburgh moved toward a housing unit known as Matilija. This unit was accessible only through an outside cage corridor bordering the juvenile facility’s main courtyard. While crossing, a group of youths and two correction officers were in the courtyard. One officer was playing basketball with two inmates, while the other talked among the youths. Their conversation halted, and they stared in silence once they noticed the tour.

Vredenburgh explained Tormey’s absence. “Because we now take in a population of 18 and above, we’re asking ourselves questions we never thought we would be asking. That kid wanted to get married, what does that look like?” Vredenburgh said, referencing California bill SB 92, signed in 2021. This bill allows minors sentenced to long-term commitments to stay until they’re 25 years old. Tormey had previously explained, “Regardless if they have a 100-year sentence, they are released back into the community at 25,” Tormey said.

The topic of officer use of force, specifically pepper spray deployments, arose a few minutes later. While 35 states and several other California counties, including Los Angeles County, have banned its use in juvenile facilities due to safety and ethics concerns, Ventura County reported over 93 instances of pepper spray use on inmates from April 2022 to June 2023. Vredenburgh defended its use, citing the potentially life-threatening danger of blunt force due to size and strength disparities among inmates and the 50/50 gender divide among the already understaffed officers, who are also required to work overtime in the VCPAJF. Not separating inmates by gang affiliation, officers argued that they need to learn to get along in the adult world. No specific details were provided on whether this VCPAJF policy increased conflict.

The group later entered a repurposed housing unit marked with a Boys and Girls Club sign. The facility included a gym, a tattoo removal station, a radio broadcasting station, a T-shirt printing design station and the Boys and Girls Club, a favorite among the incarcerated youth. Tormey emphasized the shift in methodology, from pure detention to rehabilitation and vocational training. “Now, with kids staying three, four, five years, we’re tasked with essentially raising some of these young men and women into young adults,” he said. Tormey added, “They don’t even have the fundamental life skills: How do you open a bank account? How do I drive a car? How do I get my driver’s license? So all those we’re viewing as opportunities for us to pivot and figure out what we need to do within our walls to make these people productive when they walk out the door.”

“It’s our job to protect the community, we aren’t doing our job if we don’t rehabilitate them and let them back into the community.”