American culture contributes to COVID-19 spread

It seems like the U.S. can hardly catch a break with its COVID-19 cases. We are still topping the COVID-19 World-o-meter and with little evidence of this slowing. This is especially upsetting considering that some nations, such as New Zealand, are COVID-19 free altogether, and many others, such as Singapore, have daily case numbers in the double digits. It becomes apparent that there is a correlation between the COVID-19 response of a country, at both a governmental and individual level, and the cultural views held by the country.

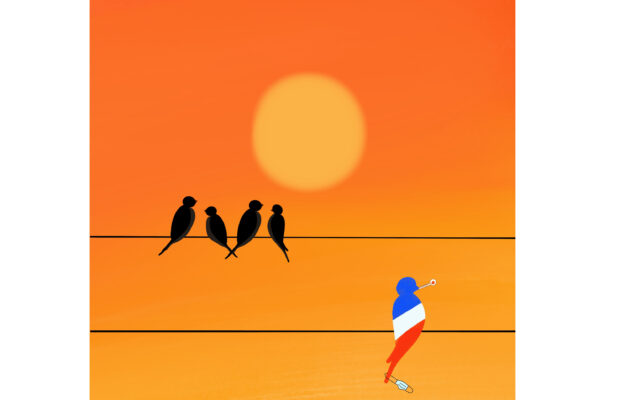

In the U.S., we have bred a culture of individualism as a byproduct of our capitalism. While there are a wide range of opinions as to whether or not this is a good thing, it is irrefutable that this has driven us into an “every man for himself” type mindset. Normally, this mindset is found in the context of socio-economic mobility. Now, that idea has been translated into not catching an illness.

If capitalism is to individualism, then socialism is to collectivism, due to the analogy of government system to mindset. Americans have become so conditioned to be afraid of collectivism and social coordination due to its close links to socialism to the point where we care more about our “personal freedoms,” such as not wearing a mask, than saving the lives of others.

The most dangerous statement told to our individualistic nation at the beginning of the pandemic was that masks are to be worn to protect those around you. Although studies have since proven that wearing a mask protects the user as well, this initial sentiment turned many off from wearing a mask to begin with simply because of the impression that it does not affect them. It is terrifying the little regard for others some of the people around us have.

Conversely, this issue does not seem to pop up nearly as much in other countries, especially those who hold more of a collectivist mindset. New Zealand, for example, was able to lock down without major opposition. Harvard Political Review reported on a study from the University of California, stating that “countries with a generally collectivist framework have a faster, more effective response, as their citizens are more likely to comply with social distancing and hygiene practices that help reduce the spread, while individualist countries respond less successively.”

Similarly, a study conducted jointly by two University of California professors and a Kent State University professor after the Ebola outbreak tested protection efficacy, the feeling that one could protect oneself from the virus, in a number of Asian collectivist societies. The protection’s efficacy was measured at three levels: personal, community and country. The results found that “collectivistic people, especially in the face of a perceived risk, tend to have a higher sense of efficacy, meaning that my group will do something to protect me or my community. And those protective processes are coordinated and work together.”

Evidently, other countries don’t experience the same political turbulence associated with collectivist efforts as the United States does. The matter here has become political whereas in other places it has remained what it is: a human rights issue. Culture is a major determinant of the spread of COVID-19 in the United States, and the lack of social coordination is preventing improvement of the situation.